Recently, a panel of experts concluded that split-thickness skin grafting (STSG) is the single most effective treatment for chronic wounds. Skin granting techniques have been reported in the literature for over 100 years. Publications by Reverdin and Thiersch first described pinch grafting and sheet grafting respectively (Ehrenfried, 1909). In 1958 Meek described a technique to expand the donor skin graft up to 10 times. The instruments were expensive, the procedure cumbersome and the grafts had to be placed with the dermal side down, therefore, it did not gain widespread use.

In 1964 Tanner described a technique for meshing skin grafts and expanding them up to nine times. Although the meshed grafts were malleable and allowed drainage, the maximally practical expansion was only six times. The technique was simple to adopt and rapidly become the standard of care. However we continue to look for graft expansion techniques that provide a larger expansion ratio, particularly in major burns, where donor sites are limited.

Eriksson’s laboratory in Boston described a new technique, in an animal model, which could provide a 100-fold or greater expansion ratio (Svensjö et al, 2002; Hackl et al, 2012; Nuutila and Eriksson, 2021). This was confirmed by Hamnerius et al (2016) and Danks (2010) clinically. All of these studies confirmed that in a moist healing environment, orientation of the grafts, dermal side up or down, was unimportant, which greatly simplified the procedure. The procedure becomes much more efficient with a non-powered, hand held dermatome and mincer (with an array of 24 circular cutting discs spaced 0.8mm apart), and can be performed in a wound care clinic or even at the patient’s bedside under local anaesthesia.. This by-passes the current skin grafting routine done by a surgeon in an operating room, usually under general anaesthesia.

Aim

This case series aims to explore the possibility of outpatient skin grafting of patients with chronic/hard-to-heal wounds using small donor sites and to gain a large expansion ratio.

Method

This was a prospective study of lower leg chronic/hard-to-heal ulcers. Comorbidities were carefully recorded and treated as optimally as possibly. The patients were then scheduled for outpatient surgery.

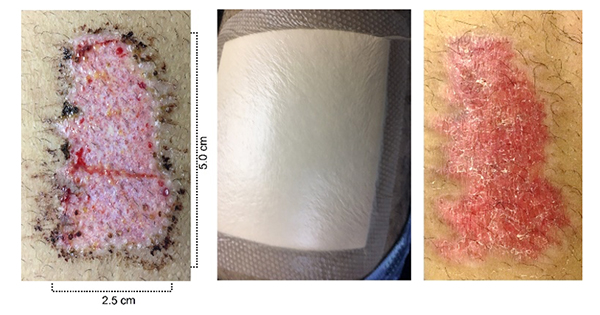

All the patients were completely debrided before entering the study. The donor site was the upper thigh, with a prefixed size of 2.5cm x 5cm (12.5cm2). The donor sites dressings were Mepilex Border (Mölnlycke) and they were changed at postoperative day 7 and again at postoperative day 14, if needed (Figure 1).

After antiseptic treatment of the donor site and the wound with chlorhexidine, the donor site and the perimeter of the wound were infiltrated with 0.5% lidocaine with epinephrine. The skin graft was taken using a hand-held dermatome. It was then placed on a hard silicone cutting board and the mincer was passed over the graft in perpendicular directions approximately 20 times. This provided micrografts with an average size of 0.8×0.8mm. The grafts were then placed in a sterile plate and hydrogel was added. After mixing the grafts into the hydrogel, the grafts were spread evenly over the wound with a spatula (Figure 2). Mepitel (Mölnlycke), a multiperforated silicone dressing, was then applied as an interface dressing. An additional 3mm of hydrogel was then applied, followed by a moist foam dressing (Mepilex®, Mölnlycke). Additional gauze and a compressive wrap was then applied. The Mepitel interface dressing was left in place for 7 to 14 days as needed. The moist foam, Mepilex dressing was changed on days 3 and 7 and then weekly after that if needed. At each dressing change, additional hydrogel was added over the graft/Mepitel dressing and the wound was photographed and measured with a Silhouette V3 camera Mobile wound measurement device (ARANZ Medical).

At postoperative day 1, a sterile multiperforated silicone interface dressing (Mepitel One) was applied over the grafted area, followed by a thicker hydrogel layer to keep the grafts moist. . The Mepitel One dressing was used till postoperative day 14, if required (Figure 3).

Results

A total of five wounds were included in this series, three females and two males, with ages ranging between 30 and 66 years old. The wounds had all been present for more than four weeks and the patients had been referred by their wound care physicians for surgery. Of the wounds, two were venous leg ulcers (VLU), two were caused by burn injuries and one from infectious skin erysipelas in a patient with diabetes. The mean wound size was 241.0cm2 (range: 134.8–387.7cm). Patient comorbidities are described in the case histories.Table 1 shows percentage healing over time.

Clinical cases

Case 1

A 66-year-old female with a past medical history of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, severe knee arthritis, venous insufficiency and a circular VLU present for the past 8 years. After wound bed preparation the wound measured 180.0cm2. The patient was instructed to keep her various medical problems under control, reduce weight, and use compressive therapy all the time, except when in bed. Figure 4 shows her treatment and it’s result.

Case 2

A 30-year-old female, obese, with a 7 weeks history of a third degree burn on her right foot after an accident with an open fire. After debridement, the wound size was 134.8cm2. After the grafting, the patient was instructed to continue using a compressive garment even after the whole wound was completely healed, on postoperative day 60 (Figure 5).

Case 3

A 59-year-old female with a circular VLU present for the last 20 years. The wound had never fully closed despite several treatments. Her comorbidities were hypertension, dyslipidaemia, severe chronic pain in the lower limbs, chronic oedema and peripheral venous insufficiency. After debridement, the wound size was 228.5cm2. After grafting, the patient was instructed to continue wearing a compressive garment. This patient had 68% closure at day 60 postoperatively, however, she reported that her pain had improved by at least 80% compared with the beginning of the treatment. Her last visit to our clinic, occurred after the end of the study (postoperative day 60) and before the pandemic was at postoperative day 210 when the ulcer was 96.3% closed (Figure 6).

Case 4

A 41-year-old male, obese with hypertension. The patient presented with a chronic third degree burn in lower limb (alcohol explosion) with two previous lost grafts. The patient came to our hospital two months after his accident. After debridement, the wound size was 273.8cm2. After grafting, the patient was instructed to continue using a compressive garment even after the whole wound was completely healed, on day 60 postoperatively (Figure 7).

Case 5

A 66-year-old male, with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes. He had two previous grafts treatments that had been lost and several attempts to heal with different dressings that were also unsuccessfully. This patient presented after recurrent erysipelas, with full thickness skin loss (387.7cm2 when we saw him) in his lower limb for the past 50 days. The patient complained about serious pain in his wound. He lived alone and found it very difficult to change his dressings by himself. After the procedure at 60 days, 71.7% of the wound was closed. Though it was not fully healed, the patient was very satisfied because the pain was greatly reduced. He continued to visit our ambulatory clinic till the beginning of the pandemic and at day 80 postoperatively the ulcer was 82.2% closed. After the COVID-19 pandemic we lost contact with this patient, because he lived in another city and it was very difficult for him to come back (Figure 8).

Discussion

The five cases demonstrate the feasibility of healing chronic/hard-to-heal wounds with outpatient micrografting under local anaesthesia and sedation. The procedure is straightforward and expeditious and the large expansion ratio limits the size of the donor area.

The current study shows that micrografting is not only clinically feasible but is also provides healing results similar to sheet grafting. The micrografts were expanded over 9 times; using smaller donor sites. The micrografts caused less pain and itching, less pigment changes and less scarring. The single use instruments enable any wound care practitioner to do skin grafting in the wound clinic, the office or at the bedside under local anaesthesia.

With the minced skin graft standardised procedure for autologous transplantation, using disposable instruments, more wounds could be grafted faster as they can be managed in an outpatient setting, under local anaesthesia and the cases discharged on the same day.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that in a moist environment orientation of the micrografts is unimportant (Svensjö et al, 2002). It has also been shown that with 0.8×0.8mm micrografts complete healing can be achieved in both healthy and diabetic pigs in 14 days with an expansion ratio of 100 times (Hackl et al, 2012). The feasibility of micrografting has later been confirmed in lower leg ulcers (Hamnerius et al, 2016) and burns (Danks and Lairet, 2010).

The simplicity of the procedure makes it useful in small and medium sized wounds and the possibility of a large ratio of expansion in the operating room makes it attractive in large burns.

Limitations

This was a prospective study that was not randomised and with a small number of cases. In the future, larger prospective randomised studies must be carried out. As this is a new procedure and material in our country, although authorised by ANVISA–Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency), we did not perform the procedure in acute patients with a severe clinical condition and we only performed the study on chronic/hard-to-heal ulcers of different aetiologies.

Conclusions

The minced skin grafting technique in chronic/hard-to-heal wounds is easy to perform and allows a greater expansion rate with a smaller donor site, using a disposable device. The procedure can be done under local anaesthesia and allows immediate discharge. It also seemed very promising also because of the expansion rate ranged from 10.8 to 31 times and there was a good cosmetic result, similar to a sheet graft.